By Natasha Hoff

English edit by Lidia Paes Leme and Katyanne Shoemaker

Illustration by Joana Ho

To talk about Alcatrazes, I need to talk about my history with this incredible place. It started in 2011, when I learned about the archipelago in a lecture and decided to propose a project in the region, which would be developed in the context of a course. It turned out that our project was not selected by the course, but we were invited by the staff of the ESEC Tupinambás to execute it. Thus began a partnership, a project, a final paper (a completed thesis!), and a master's degree.

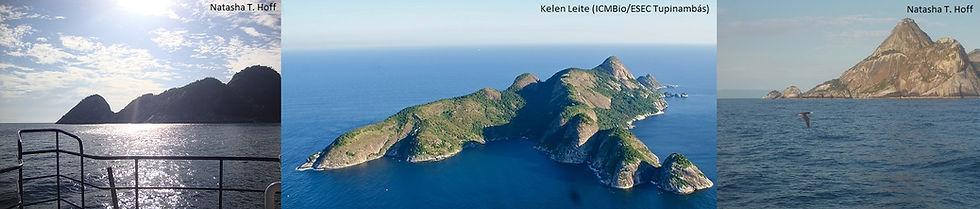

Alcatrazes archipelago, São Sebastião, Brazil

Too many unfamiliar terms and names? Well, calm down because I'm going to explain. Alcatrazes is an archipelago, predominantly rocky, formed by islands, islets, rock slabs, and patches. It is located on the northern coast of São Paulo, in the municipality of São Sebastião, approximately 43 km from the coast. The main island, the largest and more imposing than the other islands (visible from higher elevations in São Sebastião and Ilhabela), shares the archipelago name - Alcatrazes Island. And why Alcatrazes? Alcatraz is the popular name for the birds that are very abundant there. The Alcatrazes are Frigatebirds (Fregata magnificens, Image2, left), but it can also refer to another species, the Atobá, or Brown booby (Sula leucogaster, Image 2, right). It certainly is not the American island with an infamous maximum security prison! I have already received many questions about that Alcatraz Island as well…

Very abundant bird species in the Alcatrazes archipelago: Frigatebird (Fregata magnificens; left) and Brown booby (Sula leucogaster; right)

The second term that may be unfamiliar to the reader is "ESEC Tupinambás." ESEC is an abbreviation for Ecological Station, which is a type of fully protected Conservation Unit. In other words, the main objective of an ESEC is nature preservation and scientific research, and public visitation is not allowed. The Tupinambás ESEC was established in 1987 and has two nuclei. The first is formed by the Cabras and Palmas islands, which also make up the Anchieta Island archipelago, in Ubatuba. The second is composed of portions of the Alcatrazes archipelago in São Sebastião. But why only portions? I think it was a first attempt to show how important the region is, but it was not very well used by us (civil society and environmental agencies). To this day, the small protected portions remain the same. But this may change, and I will explain more about this later!

ESEC Tupinambás map, on the northern coast of São Paulo state. Source: ICMBio/ESEC Tupinambás

Last, but not least, we have the Delta area of the Brazilian Navy. This is a 710 km² area delimited around the archipelago for military training. Despite being, theoretically, important to Brazil, the shooting training brought severe negative impacts to the island of Alcatrazes, which was used as a target until 2013. Examples of these impacts include increased occurrence of successive forest fires, the suppression of about 12% of the original vegetation for the construction of support structures, and the introduction of molasses grass, an invasive exotic species. No work has been done to ascertain the effects on the marine biota. Currently, anchoring and fishing are prohibited throughout the Delta area. Although this is not its purpose, the Delta area represents the largest no-fishing zone in the coastal zone of the state of São Paulo.

Having clarified these terms, we can begin the conversation about the work that I developed during my master's degree.

When I finished my end of term paper, I realized that this place that fascinated me so much was severely lacking in basic information. So I found my opening and decided to pursue it. I had a broad idea for a project that was refined by my new advisor. I was migrating from chemical oceanography to biological oceanography (one of the wonders of being an oceanographer!), so being open to new proposals was fundamental!

The idea was to evaluate the biotic integrity of the ecosystems in the Alcatrazes archipelago region using the demersal marine ichthyofauna (also known as the bottom-dwelling marine fish community) as an indicator of the environmental quality. I am often asked: what is biotic integrity? My typical answer is that it is the extent to which an ecosystem can maintain its health, despite external influences such as ship traffic, port activity, etc.

The data I used came from three different sources:

1. A paper published in 1989 by Prof. Alfredo M. Paiva Filho (former director of the Oceanographic Institute at USP) and collaborators. This was an interesting dive into the history of work at the archipelago, as well as a glimpse into how the researcher instinct is born with us. The idea of collecting there came during a trip between Ubatuba and Santos, like one of those "clicks" of brilliant ideas we have. They went there, sampled, published, and this was the only work using demersal ichthyofauna in the area published up to that point!

2. In 2011, along with our abiotic survey, sampling was done to help in the preparation of the ESEC Management Plan (this would promote a better and more organized management of the ESEC).

3. New sampling was conducted in 2014 for this project. It was the first fishing trip for Alpha Delphini’s research boat, and it was a great experience for all of us involved!

To evaluate the data, I used two methods: the Index of Biotic Integrity (IIB) and ABC curves (Abundance Biomass Comparison). These methods were established in the 1980s, but are still extremely underused in Brazil. The IIB is based on community characteristics that are considered indicators of ecosystem health. What would these characteristics be in a so-called healthy ecosystem? A greater number of species, among which the individuals are well distributed; with a greater occurrence of top predators, here represented by elasmobranchs, and specialists regarding food (piscivores or invertivores, for example). The presence of a greater number of young individuals (not capable of reproduction) can also be considered a positive characteristic, indicating that a particular habitat may be being used as an area for feeding and growth of the fish.

On the other hand, ABC curves are based on the characteristics of the species: for example, when stressors are present, the dominant species will typically be the smaller, more numerous species with a fast reproductive cycle and short life cycle, which we call r-strategist species. Thus, we notice a greater number of organisms with small biomass, so the abundance distribution curve would predominate under the biomass curve in an impacted environment and vice versa.

We recorded 90 species of fish, 12 of which were elasmobranchs. Among them, those that occurred in the three periods and are among the most abundant were: Dactylopterus volitans (Flying Gurnard), Prionotus punctatus (Atlantic Searobin) and Pagrus pagrus (Common Seabream). These, together with more than 30 other species, are considered the accompanying fauna of the shrimp fishery in southeastern Brazil, and can be discarded, sold as a mixture, or sold separately, such as hake, angler, five species of sole, etc.

Most abundant species observed in 1986, 2011 and 2014: Dactylopterus volitans (Flying Gurnard), Prionotus punctatus (Atlantic Searobin), and Pagrus pagrus (Seabream). Credit: Natasha T. Hoff

The main results point to an environment that, although protected, is still recovering. In 1986, neither the Delta area nor the ESEC had been established. That is, there was nothing that protected the ichthyofauna of the region in any way, except for the distance from the coast. The environment was classified as poor and the abundance curve predominated under the biomass curve. The ecosystem had low species richness, one elasmobranch species (group formed by the rays, sharks, and dogfish), and low numbers of top predators (in this case, the piscivorous organisms, which feed primarily on fish).

From this time until 2011, enforcement by the ESEC was incipient and therefore I attribute the presence of the Brazilian Navy and the Delta area to the protection and improvement of environmental quality in this period. Thus, the environmental quality went from poor to moderate and the abundance and biomass curves became closer. Many more species were recorded, including elasmobranchs, which increased from one to nine species, as well as fish-eating species, etc.

As of 2011, the possibility of a more effective protection plan for the archipelago increased. This, associated with the presence of the Delta area, ensured a further improvement in environmental quality in 2014, which went from moderate to good, but the abundance and biomass curves remained close, indicating that there are still signs of stress in the fish community.

Thus, it was possible to observe that, despite the limitations of the methods and data used, the results were relevant and consistent with the history of environmental protection around the Alcatrazes archipelago and the ESEC Tupinambás, which still needs more effective protection.

With so little information about the archipelago, we decided to carry out a large bibliographic survey. We were able to map the archipelago, associating information in literature with data related to the susceptibility of each stretch of the archipelago to oil (for prevention in case an oil spill reaches the region, which I hope does not happen!) This mapping generates what we call the Environmental Sensitivity Chart to Oil Spills, or simply the SAO Chart. The chart includes information about the biota, marine currents, location of archeological sites, historical points, and the ESI (Index of Sensitivity of the Coast, which varies according to the capacity of penetration and permanence of the oil in different points of the region under study), among other relevant information.

Environmental Sensitivity Chart to Oil Spill (SAO Chart) of the Alcatrazes archipelago region, São Sebastião - SP. Note: not original scale

When making the chart, a large gap of knowledge about phytoplankton (a topic already addressed in this blog) and primary productivity, species of marine invertebrates, algae, etc. was pointed out.

Regarding the high biodiversity of the Alcatrazes archipelago, it is expected that the area will remain protected through the restrictions on fishing and boat traffic in the Brazilian Navy's Delta area, by the existence of the Tupinambás Ecological Station, and by the distance from the coast. Demersal fishing, for example, affects not only the target species, but those removed by bycatch, as well as disrupting the associated bottom surface habitats.

The Alcatrazes archipelago represents a very important coastal region, and still very little is known about it. We need to understand its ecological relationships, occupation by, and use of the area by different organisms in order to support its conservation and management.

Update: In 2016, another conservation unit was created in this area – the Alcatrazes Wildlife Refuge (REVIS) –, with 67,000 ha. The Management Plan, published in 2017, includes the register of many species occurring in the archipelago, as marine invertebrates, which was pointed out as a knowledge gap in the text. Public visitation is also allowed now (excluding the ESEC Tupinambás zones) and ruled by the REVIS Public Use Plan. Nowadays, military training uses only the Sapata Island, which was excluded from the REVIS.

Want to know more?

Conservation units:

http://www.mma.gov.br/areas-protegidas/unidades-de-conservacao

ESEC Tupinambás:

Leite, K. L. (2014), Gestão e integração de uma Unidade de Conservação Marinha Federal (Estação Ecológica Tupinambás) no contexto regional de gerenciamento costeiro do Estado de São Paulo, Dissertação de mestrado, Escola Nacional de Botânica Tropical, Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro.

My dissertation:

http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/21/21134/tde-22092015-135056/pt-br.php

Accompanying fauna and shrimp fisheries:

Graça Lopes, R., A. R. G. Tomás, S. L. S. Tutui, E. S. Rodrigues, & A. Puzzi (2002), Fauna acompanhante da pesca camaroeira no litoral do estado de São Paulo, Brasil, B. Inst. Pesca, São Paulo, 28(2), 173–188.

Sedrez, M. C., J. O. Branco, F. Freitas Júnior, H. S. Monteiro, & E. Barbieri (2013), Ichthyofauna bycatch of sea-bob shrimp (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri) fishing in the town of Porto Belo, SC, Brazil, Biota Neotrop., 13(1), 165–175.

Vianna, M., F. E. S. Costa, & C. N. Ferreira (2004), Length-weight relationship of fish caught as by-catch by shrimp fishery in the southeastern coast of Brazil, B. Inst. Pesca, São Paulo, 30(1), 81–85.

About the author:

Natasha has a bachelor's degree in Oceanography from the University of São Paulo (USP), and a master's degree and PhD in Sciences (Oceanography, Biological Oceanography concentration area) also from USP. Currently, she is a post-doctoral researcher at the same university’s Oceanographic Institute.

Comments